Garages of the Valley

Mason Bates

Piano Concerto No. 2 in F minor, Op. 21

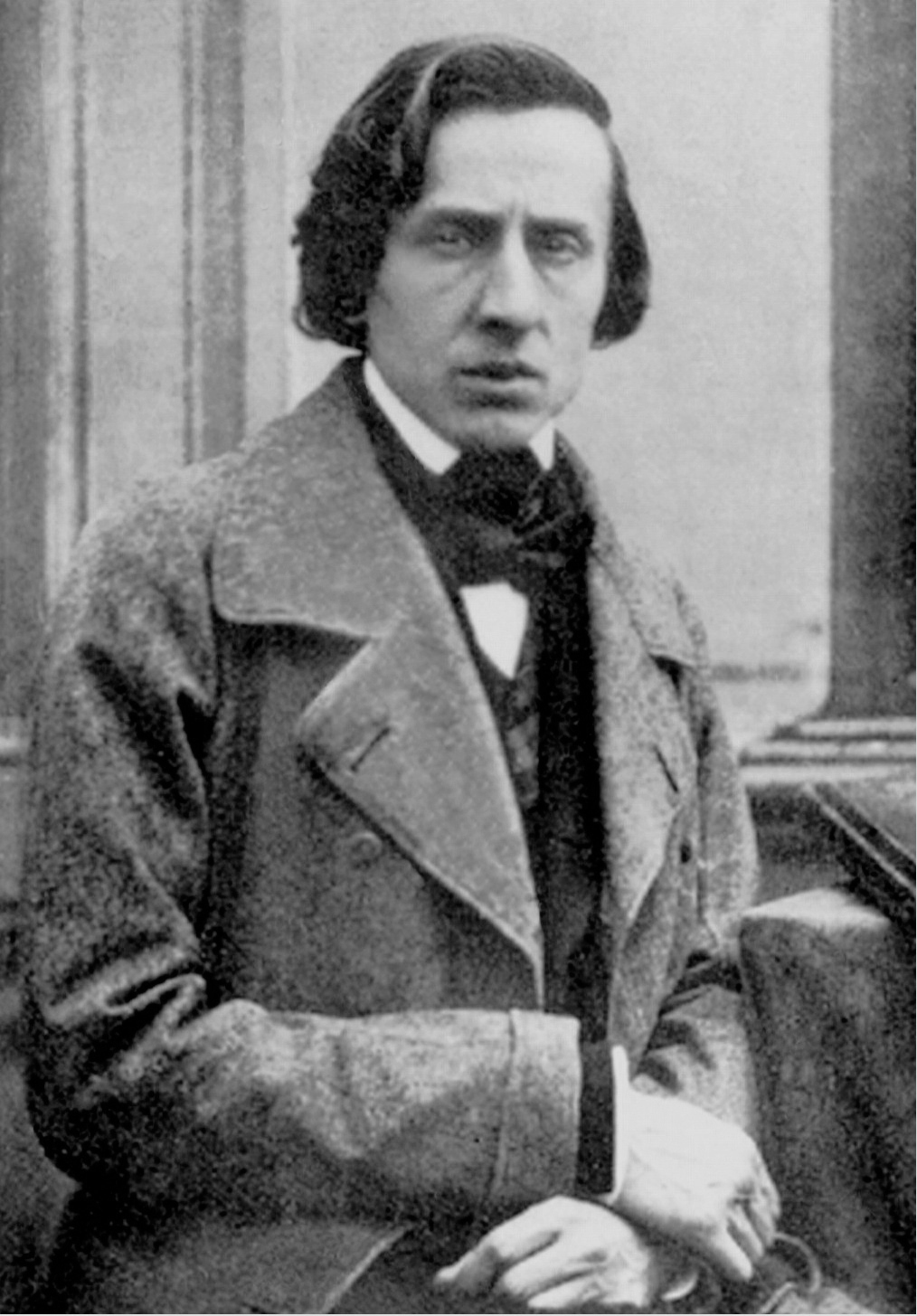

Frederic Chopin

Born March 1, 1810, in Zelazowa Wola, near Warsaw, Poland

Died October 17, 1849, in Paris, France

This work was premiered on March 17, 1830, in Warsaw with the composer as soloist. It is scored for solo piano, two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, trombone, timpani, and strings.

Frederic Chopin was the proverbial man without a country. His father was a tutor to the Polish Countess Justyna Skarbek’s son and was well connected in aristocratic circles. As a young child Chopin was able to study piano with the best teachers available. After finishing high school in 1826, he attended classes at the University of Warsaw, specializing in composition – not piano performance. In 1829, having learned all he could in Warsaw, the young Chopin decided to study abroad, but the Education Ministry would not approve his funding request. However, he was able to cobble together enough money for a short vacation to Vienna where he performed to such acclaim that he realized that private funding might be his best option. Although there was little certainty in this plan, it was his only hope. On November 1, 1830, just months after returning, he set out again from Poland for Vienna as the first stop on a planned European tour to seek fame as a composer/pianist. Within a year, he was in Paris. He would never return to his homeland. Read more >> Chopin found solace in Parisian musical life, which was much more suited to his many short salon pieces than was Vienna’s more elitist musical community. In Paris he could socialize with poets, novelists, and other musicians, while his skills as a pianist were in great demand. Tales of his performances are legendary, but such information is based on accounts of fewer than a dozen appearances. Despite his disdain for the concert hall, he composed hundreds of intimate works for piano solo, most of which have never left the repertoire. He was so dedicated to his instrument that every work he composed included the piano. After contracting tuberculosis in 1839, Chopin would live the remaining decade of his life in varying degrees of frailty. He avoided balmy weather, spending his summers at the country estate of his lover George Sand (the pen name of female writer Amandine-Aurore-Lucile Dupin), then returning to Paris in October. Although his music is often performed with great bombast, the most difficult task for the performer is to refrain from doing so, as one must remember that Chopin’s diminutive size and sickly condition would have precluded such an interpretation on his part. In place of physical power, Chopin’s music has a delicacy of ornamentation and harmonic shading shared by few composers of his day. Historians are quick to state that Chopin’s musical tastes were quite conservative. Nearly all of his music for solo piano is written in a compact form – nocturne, mazurka, waltz, etc. However, many of these forms were quite new and their use for salon music was quietly revolutionary. In his concertos, Chopin saw the orchestra as a means of conveying his piano solos on a grand scale. He has also been criticized for a lack of orchestrational skill as compared to Wagner or Berlioz (both of whom he vilified as being too cutting-edge), but Chopin created suitable and functional accompaniments that serve to enhance the decidedly progressive piano writing, which was his sole purpose in composing for orchestra. In March of 1830, Chopin premiered his Piano Concerto No. 2 (written and premiered first) at his first public appearance in Warsaw. Although the work is numbered as his second, it was the first he composed and premiered, but was published after his Concert No. 1. Chopin’s Piano Concerto No. 2 opens with a long orchestral introduction that has been described as “dutiful” with its mazurka rhythms and dramatic declamation. The orchestra introduces both themes of the movement. Once the piano enters, the orchestra recedes into a supporting role. The seemingly ordinary thematic material introduced by the orchestra is transformed into majestic and poetic music by the soloist. As expected, the usual dramatic interplay between piano and orchestra is present, but Chopin gives the soloist the lion’s share of responsibility, filling nearly every measure with dazzling pianistic figurations. The larghetto second movement opens with a brief evocative introduction. The piano enters with a theme that is reminiscent of his miniature masterpieces. Filled with long and luxuriant themes, this movement features the luminous harmonies and rhapsodic ornamentation that characterize Chopin’s music at its finest. Perhaps the most striking feature of the final rondo is the straightforwardness of Chopin’s musical language. The lavish ornamentation of the larghetto is replaced with the lively rhythms of Polish folk dances – most notably the mazurka and kujawiak. As in the first movement, the piano dominates the finale. Like Chopin’s other concerto, this movement grows more complex as it progresses. The final measures of the coda bustle with blazing scales and arpeggios that leave the audience enthralled and the soloist exhausted. << Read less

Symphony No. 4 in D Minor, Op. 120

Robert Schumann

Born June 8, 1810, in Zwickau, Saxony, Germany

Died July 29, 1856, in Endenich, near Bonn, Germany

This work received its first performance on December 6, 1841, in Leipzig, under the baton of conductor Ferdinand David. Schumann abandoned the piece, only to resurrect and revise it, eventually conducting a new premiere on March 1, 1852, in Düsseldorf. It is scored for woodwinds in pairs, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, timpani, and strings.

Tracing the dates of Robert Schumann’s compositions sometimes yields interesting results. It is widely known that 1840 was Schumann’s Liederjahr, or ‘song year,’ when he wrote the song cycles Dichterliebe, Frauenliebe und -leben, and the Liederkreis on texts of Heinrich Heine. Similarly, the following year was one of instrumental music with the first and fourth symphonies and the Piano Concerto in A minor.

The numbering of Robert Schumann’s symphonies is the subject of much confusion. The second of his works bearing the title of symphony appeared in 1841, but was received with indifference by the audience at the premiere on December 6, 1841. Although the failure was largely due to its overshadowing by a performance by the fiery virtuoso Franz Liszt on the same program, Schumann promptly withdrew the work only to return to it twelve years later and revise it as his Fourth Symphony. Two additional symphonies had been composed in the meantime. Therefore, Schumann’s Fourth Symphony of 1841, revised in 1851, was actually the second in order of composition. Read more >> Despite the order or numbering system, the work is a dazzling piece that illustrates the Romantic triumph of the creative soul over adversity. This magnificent work was written as Schumann was struggling against syphilitic insanity – a devastating symptom of the disease that would claim his life in a decade. Perhaps the most troublesome side-effects of syphilis for Schumann were tinnitus (constant ringing of the ears) and musical hallucinations, which he claimed was dictation from the ghost of Franz Schubert. He re-orchestrated the Fourth Symphony with a constant ringing in his ears. In Schumann’s evocative introduction to the first movement, the themes seem to materialize gradually, slowly taking shape before the listener. The allegro opens vigorously with a statement of the main theme, which will return as a cyclic element throughout the symphony. As the movement unfolds, the key transforms from the shadowy D minor to a dazzling D major. Schumann’s sentimental Romanze is a lovely gesture of Romanticism, emphasizing the many contrasts of orchestral texture while exploring the tender beauties of lyricism. The energetic and heavy-handed scherzo theme is a clever variation of the cyclic melody from the first movement. Schumann’s central trio section is a gentle contrast to the rest of the scherzo. A slow introduction connects the scherzo to the dramatic finale. Schumann returns to material from each preceding movement, much like Beethoven did in the finale of his Ninth Symphony. A majestic horn fanfare ushers in a brilliantly rustic theme just before the final buildup unveils an exuberant conclusion. << Read less