Brundibár

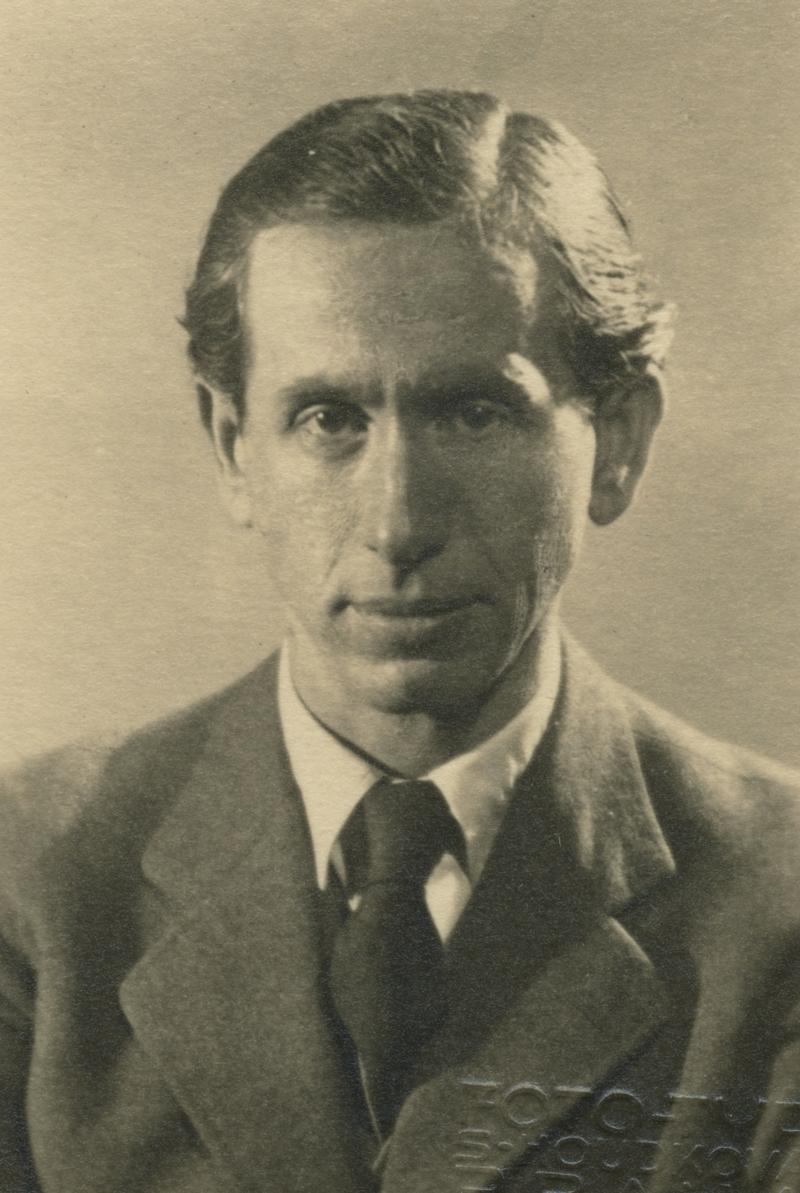

Hans Krása

Born November 30, 1899, in Prague, Bohemia (present-day Czech Republic)

Died October 17, 1944, in Auschwitz, Poland

This opera was premiered in November 1942 at the Hagibor Orphanage in Prague, but was more famously performed on September 23, 1944, at the Terezin ghetto by inmates of the Terezin transit camp. The original version is scored for children’s choir from which 10 major roles are drawn, piccolo, flute, two clarinets, trumpet, percussion, piano, strings, and onstage accordion.

Hans Krása was an immensely talented composer whose memory has been overshadowed by his death in Auschwitz, but there is much more to Krása than this. Born to a wealthy Jewish family, he was trained in piano and violin at the German Music Academy in Prague. While there he became friends with Alexander Zemlinsky who later worked with him in Berlin. Krása’s musical influences became that of Zemlinsky’s inner circle—including Mahler and Schoenberg. He enjoyed German attention to detail, but was also drawn to the frivolity of many of the French composers of the day. Read more >> After returning home to Prague in the late 1920s, Krása first concentrated on smaller works, but soon began to write for the theatre, where he had long worked as a rehearsal conductor. His opera, Betrothal in a Dream, became especially popular and was honored by the Czech government. His music is divided between works for voice (operas, cantatas, lieder) and chamber works. There is also a symphony and overture, both for small orchestra. Like so many Jewish people in the 1930s and ‘40s (as well as members of the LGBTQIA, Catholic, and anti-Nazi communities), Krása was confined by the German government. In his case, he was sent to the Terezin transit camp, sometimes called Theresienstadt. Terezin, while essentially a temporary holding area for those who were to be sent to a concentration camp, eventually became the model camp that the Nazis showed to the Red Cross and others who suspected that these facilities were there for extermination. At Terezin storefronts and public areas were maintained to look like a normal village. The propagandists called it a “paradise for Jews” that was a gift from the Führer, himself. Of course, these lies covered the reality that inmates were not allowed to use the luxurious amenities. However, a certain number of musical performances were permitted to take place. In 1943-44 over 12,000 prisoners were moved from Theresienstadt to the Terezin family camp at nearby Auschwitz, one of over a dozen sub-camps there. Before long, other prisoners from different countries joined them. Of the total 17,500 prisoners at the Terezin family camp, only 1,294 survived. Hans Krása perished. The last work Krása finished before his arrest was the children’s opera Brundibár. Composed in 1938 for a government competition, this work has a libretto by Adolf Hoffmeister. The first performance in the winter of 1942 was at a Jewish orphanage for children whose parents were interned. Krása missed the premiere, as he was already at Theresienstadt. Within six months, the entire cast of children had joined Krása at the camp, so the composer reconstructed the score from memory and scored it for available instruments. After the Terezin premiere in the fall of 1943, the work would be performed 55 times the next year. Video footage exists of these performances in a propaganda film the Nazis made to falsely show the Red Cross that they were not mistreating Jewish people. The plot, as described by the publisher, is clearly anti-Nazi: “Aninka and Pepicek go to the market to get some milk for their sick mother. As they don’t have any money, they decide to follow the example of the organ grinder, Brundibár – people throw coins in his hat when he makes music. Aninka and Pepicek sing their favorite song but nobody listens to them. When they try to draw attention to themselves, they are chased away from the market for being a nuisance. It is almost dusk. Aninka and Pepicek don’t know what to do. How can they sing louder than the bad old organ grinder with their small voices? Lots of children must sing – that might work. At this cue, a dog, a cat, and a sparrow are on the spot and promise to help. The next morning, the animals round up all the children in town, who make a large choir. The plan succeeds: their singing is louder than the barrel organ, the people listen, and soon Pepicek’s cap is full of coins. Suddenly, Brundibár appears, grabs the cap from Pepicek, and tries to run away with the money. However, he is only one against many and he doesn´t stand a chance. The children celebrate their victory and the choir sings of friendship and support for each other.” << Read less

Incidental Music to Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream

Felix Mendelssohn

Born February 3, 1809, in Hamburg, Germany

Died November 4, 1847, in Leipzig, Germany

This work was first performed, as a whole, on October 14, 1843, at the court of King Frederick Wilhelm IV of Prussia in Potsdam. The Overture had been premiered on February 20, 1827. It is scored for pairs of flutes, oboes, clarinets, bassoons, and horns, with three trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, and strings.

Much attention is given to the remarkably young age at which Mozart composed his earliest works, unfortunately overshadowed the equally amazing talents of the young Felix Mendelssohn. Mozart was forced to tour Europe as a young child, playing for kings, popes, and princes. Mendelssohn showed his talent at a similarly young age, so his banker father invested in the best music teachers available for Felix and his musically gifted sister Fanny (who was also a gifted composer). As the young Felix composed, he regularly heard his music performed by a private orchestra that played in the Mendelssohn’s Berlin home every Sunday. This invaluable advantage allowed the young composer to develop a musical identity and adeptness for orchestration before his age reached double digits. Thirteen early “string symphonies” date from this period – all written before he composed his first numbered symphony at the age of fifteen.

Read more >> For a set of pieces composed over fifteen years apart, there is amazing continuity throughout the thirteen sections of the score. However, complete performances are rare, with most concentrating, instead, on a suite of four pieces – Overture, Scherzo, Nocturne, and Wedding March – with other movements added as needed. This performance features Mendelssohn’s entire score. A brief description of each section follows: Mendelssohn’s sonata-form Overture begins with four soft chords followed by brisk and otherworldly music in the high strings, ushering in the magical fairy world of the play. Of special interest is the humorous effect caused by the downward leaps in the main theme, calling to mind the bray of Bottom with the donkey’s head. The next section is the scherzo, which appears at the end of Act I. This music is trippingly light, featuring an extended flute solo near the end – a perfect accompaniment to Puck’s conversation with a fairy at the opening of Act II. The second act continues with music accompanying the Bard’s immortal verses in a technique called melodrama (which is akin to the practice of underscoring a scene in a movie). Mendelssohn’s fairy world is populated by light flute textures supported by strings. This in especially apparent in the Elfenmarsch (Fairies’ March) that occurs as the scene continues. Act II, Scene 2, opens with Titania and the fairies, portrayed here by two solo sopranos and women’s chorus. First Fairy: You spotted snakes with double tongue, All: Philomel, with melody Second Fairy: Weaving spiders, come not here; All: Philomel, with melody, Sing in our sweet lullaby; Never harm, First and Second Fairies: Hence, away! now all is well: Another melodrama follows as woodwinds, violins, and basses underscore the remainder of the scene. Mendelssohn’s Intermezzo was designated for the interval between Acts II and III. It is in two parts, the first representing Hermia’s nightmare of the serpent and the second portraying a rustic country dance, featuring a pair of comical bassoons. The astounding ability of Mendelssohn to capture the intricacies of an array of different characters is especially apparent at the beginning of Act III. In this scene, a group of craftsmen are rehearsing a play and haggling over the details. This scene connects directly to the magical and peaceful Nocturne in which a wistful French horn solo captures the enchantment of the Athenian forest at night. The last half of Act IV, Scene 1, is cast as a melodrama as Titania awakes and Bottom is changed back to his human form. Oberon calls for music, which sounds as the sun rises. Mendelssohn’s eternal Wedding March has become one of the most familiar orchestral pieces in history, but originally it introduced the wedding of Theseus and Hippolyta. The next melodrama includes a brief funeral march, which is followed by the contrasting Ein Tanz von Rüpeln (A Dance of the Clowns) as heard in the overture. A final melodrama includes a reprise of the Wedding March. Mendelssohn’s finale includes the chorus singing the valediction of Oberon and Titania as this magical play comes to an enchanted conclusion. Chorus: Through the house give gathering light, First, rehearse your song by rote << Read less

Thorny hedgehogs, be not seen;

Newts and blind-worms, do no wrong,

Come not near our fairy queen.

Sing in our sweet lullaby;

Lulla, lulla, lullaby, lulla, lulla, lullaby:

Never harm,

Nor spell nor charm,

Come our lovely lady nigh;

So, good night, with lullaby.

Hence, you long-legg’d spinners, hence!

Beetles black, approach not near;

Worm nor snail, do no offence.

Lulla, lulla, lullaby, lulla, lulla, lullaby.

Nor spell nor charm,

Come our lovely lady nigh;

So, good night, with lullaby.

One aloof stand sentinel.

By the dead and drowsy fire:

Every elf and fairy sprite

Hop as light as bird from brier;

And this ditty, after me,

Sing, and dance it trippingly.

To each word a warbling note:

Hand in hand, with fairy grace,

Will we sing, and bless this place.