PROGRAM NOTES

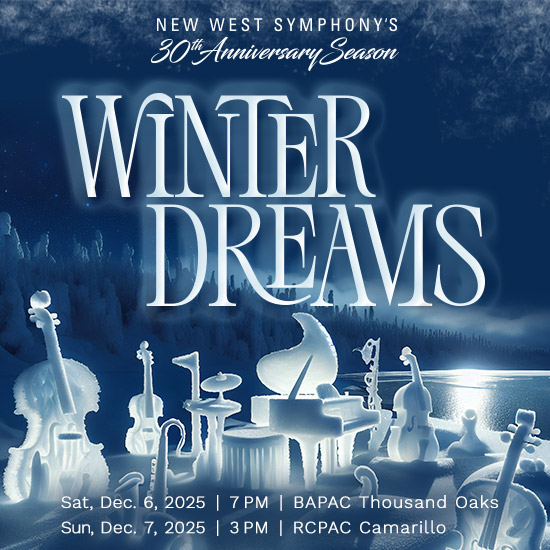

Winter Dreams

Nutcracker Suite

At Christmas 1960, the composing duo of Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn managed something truly extraordinary: a successful reimagining of The Nutcracker Suite. This suite was first composed as a ballet score by Russian composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky in 1892. It wasn’t until 68 years later that Ellington and Strayhorn released their own version, refocused through the lens of big band jazz.

Ohio born, Billy Strayhorn, was a 25-year collaborator with Duke Ellington. Strayhorn’s compositional contribution to Ellington’s legacy includes “Take the ‘A’ Train” and “Lush Life.” Early in life he strived to be a classical composer, but via introductions to Art Tatum and Teddy Wilson, Strayhorn focus shifted to jazz. Ellington would describe Strayhorn as “my right arm, my left arm, all the eyes in the back of my head, my brain waves in his head, and his in mine.”

Duke Ellington was born at the turn of the 20th century in Washington DC and would go on to write or collaborate on more than one thousand compositions. Ellington defied being type cast as a jazz composer and embraced the notion of writing American Music “beyond category.” Ellington lived for 75 years, encompassing massive shifts in recording, television, travel, and categories of popular music. He is a fourteen-time Grammy Award winner, was bestowed the Presidential Medal of Freedom, numerous honorary degrees, and a Pulitzer Prize.

In his original liner notes for the Ellington-Strayhorn Nutcracker Suite, record producer Irving Townsend included the fantastic fiction that Ellington met Tchaikovsky while Ellington’s orchestra was performing at the Riviera Hotel in Las Vegas. Knowing that the Russian died in 1893, a full six years before the American was born, this meeting never could have happened in the literal sense. However, listening to the jazzed-up Nutcracker, one could imagine the work as a meeting place for the three great composers, separated by oceans and decades, but communicating through art.

Ellington and Strayhorn did not simply place jazz rhythms over Tchaikovsky’s music. Instead, they picked up the notes, recast the beats, communed with the themes, and recreated the work, turning it into something that was at once completely their own and completely Tchaikovsky’s. In doing so, they showed that while music may be the universal language, it is spoken with many accents (and therein lies the fun).

Las Posadas

A treasured Christie family memory is from mid-December in the freezing Plaza of Santa Fe, New Mexico, where we were unexpectedly introduced to the beautiful Las Posadas tradition. We laughed at the response of the gathered crowd raucously jeering at the “innkeepers” turning away the young couple representing Jesus and a very pregnant Mary as they sought refuge during their journey.

Dating back over 400 years from a region outside of Mexico City, Las Posadas is a nine-day celebration representing the nine months of Mary’s (the Mother of Jesus Christ) pregnancy. Two actors dress as Mary and Joseph and process to various homes, representing possible Inns. The procession of musicians and spectators sing Posadas songs, with many carrying star shaped piñatas and paper lanterns. During the procession, the group is turned away until reaching the designated Posada (shelter), where a celebration of prayer and traditional food is shared.

Like so many traditions with their origins around the Winter Solstice, Las Posadas is the merger of the Aztec celebration of Tonantzin (mother of the Gods) and birth of the Sun God Huitzilpochtli, and the parallel celebration of Advent in the Christian tradition.

I am grateful to composer Fernando Arroyo Lascurain for creating a Los Posadas “mini celebration” for the symphony and Los Robles Children’s Choir to represent an important tradition for our region. There are many locations throughout west Ventura County who have Las Posadas as part of their holiday celebration. I encourage you to experience them as part of your holiday calendar.

©2025. Michael Christie