A Great Circle (World Premiere Commission)

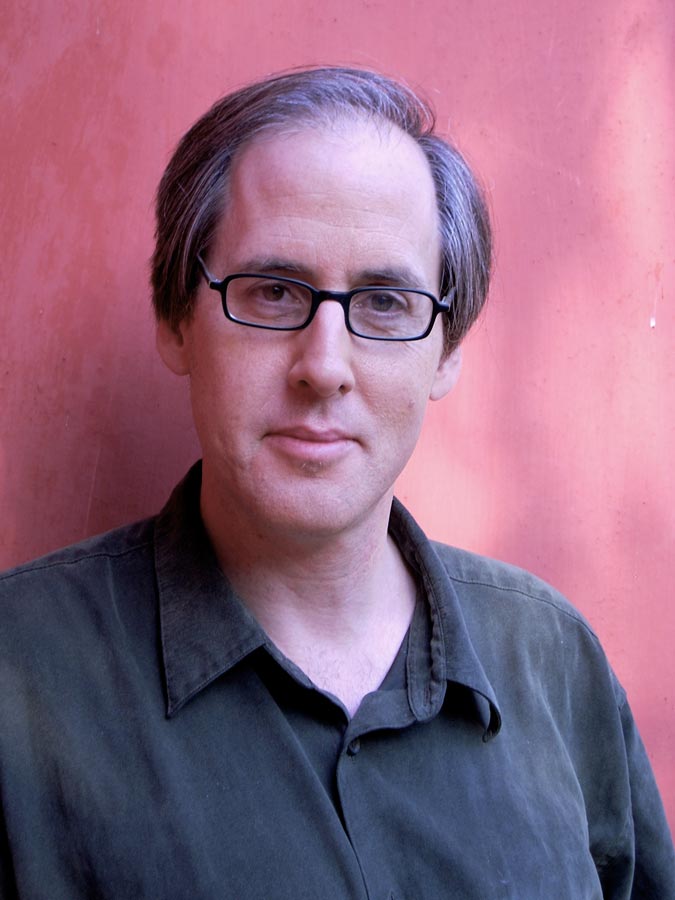

Jeff Beal

Born June 20, 1963, in Hayward, California.

This work premieres January 26 & 27 with the New West Symphony.

Jeff Beal is a composer with a genre-defying musical fluidity. His film scores have received critical acclaim, while he remains a respected composer in the concert, theater and dance worlds. Beal’s The Great Circle was commissioned by the New West Symphony for its premiere performance at this concert. The composer provided a very detailed description of the various influences that inspired this music.

“The Great Circle is a musical narrative in five parts, written in response to the Thomas Fire, and the Montecito mudslides of 2017-18. Read more >> “It is a piece about the complexity of our dance with our natural environment; i.e. the power of nature to both destroy and also regenerate itself. It is a mediation on the suffering and compassion the community experienced during these times; an invitation to reflect on the past, the forces and elements, which also allow life to return in our future. The title comes from a poem by Wendell Berry…” In the great circle, dancing in When you meet the destined ones When you meet, and hold love ~ Wendell Berry, 1982 “Our Children, Coming of Age” The Great Circle is a powerful orchestra work cast in five movements, entitled Earth, Air, Fire, Water, and (Re)birth. Beal provided some insight into the meaning behind the titles: Composer biography and quotes provided. << Read less

and out of time, you move now

toward your partners, answering

the music suddenly audible to you

that only carried you before

and will carry you again.

now dancing toward you,

out of your awareness for the time,

we whom you know, others we remember

whom you do not remember, others

forgotten by us all.

in your arms, regardless of all,

the unknown will dance away from you

toward the horizon of light.

Our names will flutter

on these hills like little fires.

Concerto No. 5 in A Major for Violin and Orchestra, K.219, “Turkish”

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Born January 27, 1756 in Salzburg, Austria

Died December 5, 1791 in Vienna, Austria

The work was probably first performed in late December 1775 at the court of the Prince Archbishop of Salzburg, with the composer as soloist. It is scored for two oboes, two horns, solo violin, and strings.

As a child, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was well known as a violinist and keyboard prodigy, touring Europe while performing for every major crowned head on the continent. As he physically grew into his teenage years, he could no longer pass as a precocious child and was forced to settle down to a court position. As concertmaster of the court orchestra for the Prince Archbishop of Salzburg, he was able to explore the sounds of the orchestra firsthand. The position also allowed him to concentrate on his violin playing. Although he came to despise the job that he would eventually leave to seek his fortune in Vienna, the Salzburg years saw the composition of his earliest masterpieces. Read more >> During his nineteenth year (1775), Mozart composed the last four of his five violin concertos. Written for his own use, these delightful works were soon on programs featuring other violinists, most notably Antonio Brunetti who succeeded Mozart as concertmaster. The works have never left the repertoire in the almost 230 years since their composition. True to his playful sense of humor, Mozart filled the fifth concerto with many lighter moments. The extreme number of themes presented here is even unusual for the ever-flowing pen of Mozart. He also toys with our expectations. What begins as a normal orchestral introduction, with the presentation of both themes, is turned on its head when the soloist enters at a dramatically slower tempo. When the momentum resumes a few measures later, the soloist plays a completely different melody simultaneously with the one the orchestra introduced at the beginning of the movement. In fact, we discover that we have only heard the accompaniment until the violinist enters with the real first theme. Such a departure was revolutionary and would certainly have been noticed by eighteenth century audiences. Mozart’s adagio second movement emphasizes the legato singing quality of the violin. Long phrases allow the soloist to emphasize the beauty of the instrument while ornamenting the melody. The finale begins as a reserved minuet led by the soloist. Classical balance and restraint prevail here as the violinist dances around the staid theme in elaborate flights of fancy. A central section switches to an allegro 2/4 meter with the strongly accented downbeats, wide melodic leaps, and bass drones that define the “alla turca” style that give this concerto its nickname. The final section of the movement is a restatement of the opening minuet, but with a more elaborate solo part, reflecting the youthful exuberance of a teenage composer ready to develop into a timeless master. << Read less

Symphony No. 7 in A Major, Op. 92

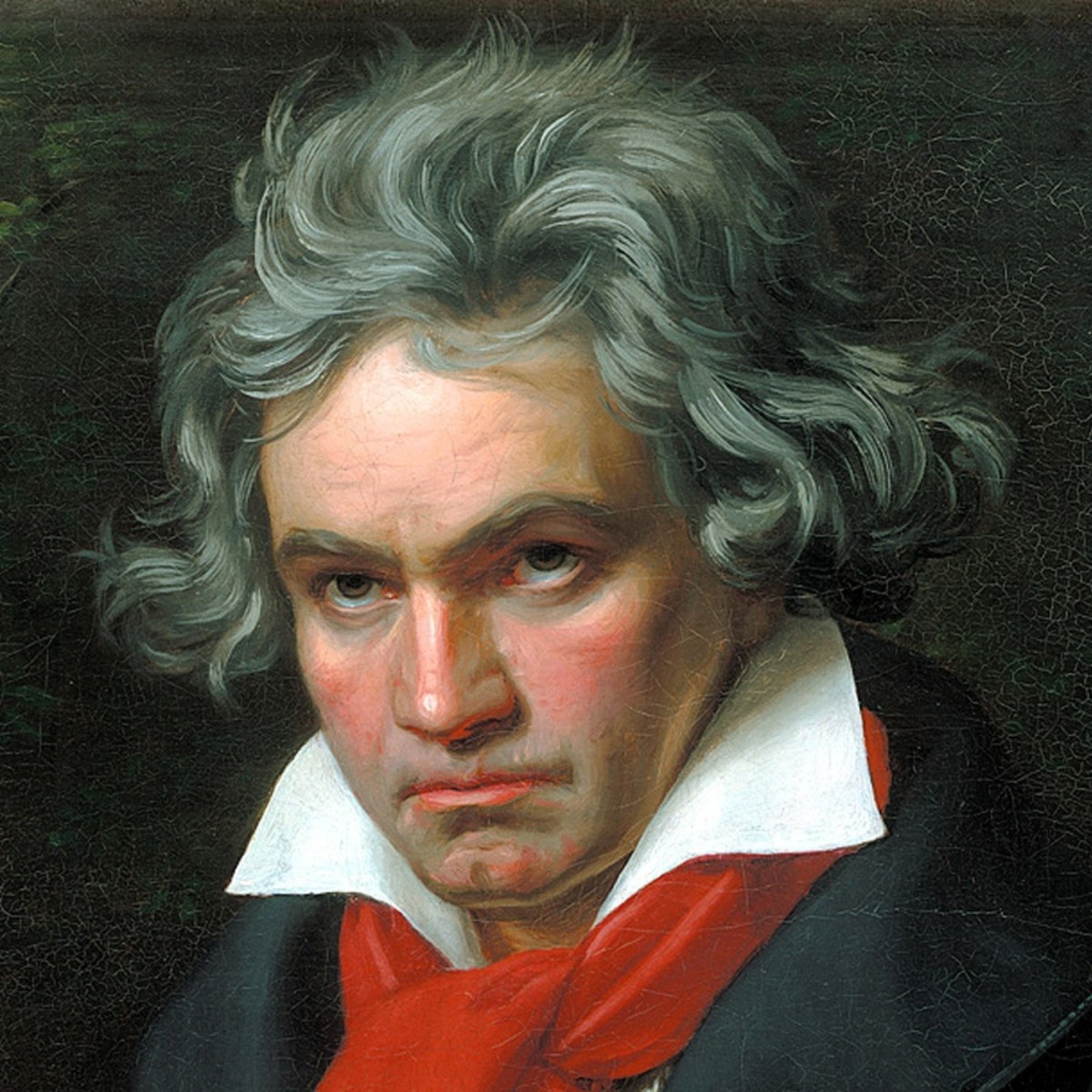

Ludwig van Beethoven

Born December 16, 1770, in Bonn, Germany

Died March 26, 1827, in Vienna, Austria

This work was first performed on December 8, 1813, in the Hall of the University of Vienna. It is scored for pairs of woodwinds, horns, and trumpets, with timpani and strings.

Ludwig van Beethoven’s works are grouped into three periods. The Early Period ends about 1802, and includes the works from his hometown of Bonn, where Beethoven lived until 1792, and all of his music from his first decade in Vienna (1792-1802). Music from the Early Period is largely classical in structure – much like the later works of Haydn and Mozart. Even though the music rarely approaches the storminess of his later works, it often sounds as if dark clouds are threatening on the horizon. The Second Period (1802-1812), often called the Heroic Period, includes the first eight symphonies, all of the concerti, and his opera Fidelio. This music often features bold contrasts and often deals with revolutionary subjects. It was during this time that Beethoven faced impending deafness. Largely coinciding with his thirties, this is the period that saw Beethoven’s reputation grow and his hearing almost completely disappear. The Late Period (1812-1827) produced fewer works, but the ones he did compose were of the most profound nature, and were often misunderstood by his public. Perhaps most notable of these were the Missa Solemnis and the Ninth Symphony. Beethoven faced many personal demons in the Late Period, especially his long battle to gain guardianship of his nephew and his increasingly reclusive lifestyle. Read more >> The symphonies of Beethoven are for many the cornerstone of the Western symphonic tradition. These nine works span nearly his entire professional life, encompassing all three periods of his compositional output. Written three full years after the Pastoral Symphony, the Symphony No. 7, composed in 1811-12, is one of the final major works of the Heroic Period. Its premiere took place on December 8, 1813, at a benefit concert for Austrian and Bavarian soldiers wounded in the Battle of Hanau fighting against Napoleon. Interestingly, the Symphony No. 7 received a less enthusiastic ovation than did Beethoven’s Battle Symphony Wellington’s Victory – a work revived today only as an occasional historical curiosity. The Seventh Symphony is now universally regarded as one of Beethoven’s most significant works. This symphony is in four movements, beginning with a slow introduction. This opening is quite extensive, with a famous oboe solo and an extended transition to the quicker main section of the movement. Beethoven, showing one of his trademark gestures, sets up anticipation for the fast section ten measures before it actually occurs. When it finally arrives, the lively theme, featuring sprightly dotted rhythms, is presented by the flute and oboe. The slow dirge-like beginning of the second movement, set in variation form, begins with one of Beethoven’s most skillful gestures. The listener struggles to find the melody, but it is elusive. The repeated monotone acts as a kind of anti-melody. By using this technique, Beethoven draws us inside the music. The result is one of the most electrifying moments in Beethoven. The Scherzo, marked Presto, is an example of the composer’s fondness for unsophisticated humor, with its contrast of the lumbering opening theme to the response in the high woodwinds. There are abrupt shifts in the harmony that add an almost boorish effect. The elegant trio interrupts the festivities, only to be overpowered by a return of the main theme of the Scherzo. The finale uses a traditional sonata form with a coda but is progressive in its shifting of emphasis to the second beat of the measure to end the symphony with an irresistible burst of energy. << Read less